Think about any sport or competitive activity, whether that’s football or a spelling bee. They always feature at least one person who acts as a moderator, referee, or judge. With their domain expertise, this person watches everyone’s behavior and constantly compares that against a set of rules. If someone crosses that threshold, they blow a whistle or throw up a flag. They are, in effect, saying that things have gone from OK to not OK.

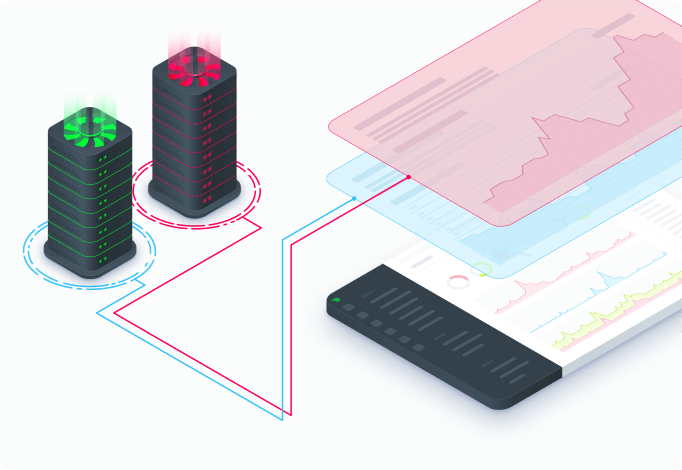

Deploying an application, running an infrastructure, or even keeping tabs on a single virtual machine (VM) running on a cloud provider is much like playing one of these games or sports. There are a lot of moving parts, but there are also distinct thresholds between OK and not OK.

- A system running at 99% CPU is not OK.

- A MySQL database returning 50% slow queries is not OK.

- An Apache web server returning more 503 errors than 200 successes is not OK.

- A system running at 82% CPU utilization might be OK.

- A MySQL database returning 5% slow queries might be OK.

- An Apache web server returning a few uncorrelated 503 errors might be OK.

That’s where preconfigured alarms, with smart defaults designed by people who have experience monitoring systems and mission-critical applications, provide so much immediate value. So, to nip some of the first concerns users have about alerting in the bud, like, “My customers will let me know when my website is down,” or “I don’t even know where to start with thresholds, so I’ll just use htop,” let’s look into how these systems work in Netdata.

What are alerting and alarms?

Every monitoring solution that offers these features uses slightly different terminology, but here’s the gist. Alerts or alarms are processes that compare metrics data against thresholds and let their users know when something is not OK.In the Netdata world, we also call this feature health monitoring: is your node OK or not OK right now? When Netdata’s watchdog process notices something odd, whether that’s in the underlying system, the container layer (when in play), or specific applications, it generates an alarm.

An alarm always begins with metrics data, which is stored in a time-series database (TSDB). The database stores a series of data points with the timestamp at which that data was collected to provide meaningful context for each number. A point of metrics data is only valuable when you can compare it to other points, particularly over large timeframes, which then lets you calculate averages, minimums, maximums, and deviations from “normal.”

On a regular interval, the watchdog process queries the TSDB for a bit of metrics data, and then runs a calculation on that data, such as calculating the average of 10 data points collected over the last 10 seconds. It then compares the result of that calculation against a configured threshold, and if the calculation exceeds the threshold, it raises an alarm.

For example, one of the use alarms that comes preconfigured with every Netdata installation out of disk space time. This alarm first queries the database for available disk space metrics over the last hour, then calculates the rate at which the database is filling. The alarm then calculates whether the disk will fill up soon based on that rate, and if so, fires off a warning or critical alarm.

On a monitoring platform like Netdata, this chain of query-calculate-compare happens many times every second, using a huge variety of preconfigured thresholds, attached to the most critical metrics you might want to stay aware of.

The output of alarms, whether that’s for single nodes or infrastructure of hundreds of ephemeral nodes, are notifications and actions.

Notifications are those annoying (more on that later) pop-ups or pings that you get from other software, like Slack. When it comes to monitoring the health of an infrastructure, system, container, or application, notifications are designed to notify you of a not OK situation and provide some important context to help you take action, such as the system/application affected, which metric(s) are related, which chart(s) you could look at to begin your investigation, and where the alarm is configured if you want to quickly silence an alarm or change a threshold.

Actions are a little broader in nature. They could be manual actions, such as opening up a dashboard to visualize metrics, performing root cause analysis, or running a script designed to help remedy the situation. They could also be automated, like firing off an incident response process on a platform like PagerDuty or StackPulse. Whatever form the action takes, the immediate goal is to identify the source of the problem, come up with a resolution, deploy it, and sit back as the health watchdog goes from wildly waving its arms about a not OK alarm to sitting quietly and waiting for its next time to shine.

All of the above, from the way the health watchdog queries the TSDB, to where notifications are deployed, can create two big problems—if they’re not configured properly.

- False positives: An alert telling you that a system or application is not OK, when in fact it is. These result in wasted time and resources, and lead to mistrust in the monitoring system itself.

- Alarm fatigue: A desensitization to the alerts themselves, which leads to either silencing or ignoring them altogether. Fatigue can come from bad experiences with false positives or the sheer volume of emails, Slack pings, or automated incidents created on a third-party platform.

The anatomy of Netdata’s intelligent alarms

Every alarm that ships with Netdata comes with intelligent defaults for each of these anatomical points. Because they’re designed by people who have monitored these types of systems and applications in production before, they reduce the risk of false positives, which create panic for no reason and leads to alarm fatigue.Here are a few of the ways the Netdata team, and its community of IT professionals, designs our alarms to generate useful notifications and actions:

- Metrics data: This is the raw information, stored alongside the time it was collected, about resource usage, interactions between a system’s components, or actions they’re taking. Metrics can come from hardware, the operating system, containerization layers, and the applications running on a node. In Netdata, the collection interval is every second (and at “event frequency” for eBPF metrics, meaning you see every kernel interaction, no matter how quickly they happen), giving you the most precise foundation for alarms.

- Filtering: Every alarm should only run off a specific series. For example, the Netdata alarm related to disk space only queries for the available disk space on every disk, and doesn’t bother with anything else. Filtering also allows you to run certain alarms against nodes with specific labels, hostnames, or operating systems. Filters often allow some pattern matching.

- Frequency: This is how often the alarm’s calculation is run against metrics data. Set this based on how quickly you would like to know about a fault in a particular system. While you might not need to know every 10 seconds that your disk isn’t filling up, you definitely want to know within seconds if a MySQL server crashes.

- Templates: Write once, apply everywhere. Use templates to apply a specific query and calculation to multiple metrics series without having to write the same alarm again and again. Netdata offers this via dimension templates and the ability to apply logic to multiple charts.

- Calculation: Many alarms convert the raw metrics data into another format, or compare it against a parallel metric series, in order to make the result human-readable. For example, Netdata’s active processes alarm doesn’t just alert you when the volume of processes on the system reaches X. Instead, it multiples the active processes by 100, then divides that by the system’s maximum processes (from /proc/sys/kernel/pid_max). The result is a percentage, and the alarm crosses its warning threshold at 75%.

- Thresholds: Every alarm takes queried metrics data, or a calculated result, and decides whether it’s OK or not OK. Most thresholds never change, but some monitoring platforms offer dynamic thresholds based on the system’s baseline.

- Hysteresis: This prevents floods of alarms for metrics data that is “flapping” around a configured threshold. For example, if your node’s CPU usage is between 80 and 90%, and the warning’s threshold is 85%, you’ll get flooded with notifications. A recipe for alarm fatigue. Hysteresis prevents additional alarms until the CPU usage first drops to a normal level, then comes back up again.

- Severity: Netdata uses CLEAR, WARNING, and CRITICAL alarm statuses, with CLEAR meaning the alarm is OK, and WARNING/CRITICAL meaning it’s in some state of being not OK. Severity is essential to alerting and alarms best practices.

- Advanced configuration: In Netdata, there are even more variables, syntaxes, and outputs available for the adventurous soul, some of which we use in preconfigured alarms to make them relevant and valuable.

- Recipients: To avoid alarm fatigue, organizations should audit the intended recipients of every alarm to ensure only the proper stakeholders, who have the capacity to deal with a particular issue (and are online/at work to address them), receive them.

- Platforms: Some notification platforms are “dumb,” in that they only receive a notification and display it to you; other “smart” platforms take take additional, automated action based on it. An email or Slack notification implies the recipient will take action as necessary, while an incident management platform like PagerDuty spins up new processes, such as creating a formal incident and inviting colleagues to join in troubleshooting.

- Severity: Send warning notifications to Slack for passive observation, but critical alarms to an external platform to ensure all the right players are paged and hop into a conference right away.

Ready for alarms? Some resources to get you started

If you’re ready to start monitoring the health and performance of your infrastructure, with hundreds of preconfigured alarms and entirely for free, sign up for Netdata.Once you’ve set up a node and are seeing its metrics in Netdata Cloud, read our documentation on viewing active alarms, configuring existing alarms, or enabling notifications. From there, look into every service and application Netdata integrates with, or make root cause analysis a little more fun with intelligent features like Metric Correlations.